Uma Chatterjee

“But just as we are made up of our fragility we are also made up of our abilities and unrealised strengths..”

Uma Chatterjee is a mental health professional engaged with human rights development work for almost 2 decades. She is the Co-founder and Director of Sanjog India, a non-profit which works with development issues like access to justice, law & policy reforms, gender equity and survivors leadership in social transformation. In addition, she passionately partners a leadership development and change management firm called ChangeMantras, which believes that the secret to meaningful change is to focus one's energy not only on fighting the old, but also on building the new.

When discussing one of of the biggest problems she dealt with accentuated by the global pandemic, Uma shares the impact of the lockdown on survivors of sex trafficking.

“The confinement of survivors of trafficking to their homes due to the lockdown earlier, and restricted mobility due to the pandemic, has triggered severe traumatic psychological symptoms for a community of young women in Bengal. They’ve been suffering from symptoms of body trembles, nightmares and flashbacks, severe body pains, sweat breakouts, migraines and severe bouts of depression and anxiety. Confined to their rooms and small houses in their rural communities, some of them have started getting reminded of the time when they were confined to rooms, locked up, subjected to physical and sexual torture, in forced prostitution. Their somatic symptoms have been triggered in fear and anxiety of the very same violence they experienced when they were trafficked. Our bodies remember trauma and abuse — quite literally. They respond to new situations with strategies learned during moments that were terrifying or life-threatening.”

The situation was severely stressful with hundreds of distressed migrants who returned to their villages earlier in the year. Sanjog and the frontline field organisations it partners with, received multiple SOS calls from migrant labor trafficking survivors who had made it back to their villages. Their guilt about being alive and safe at home, while other family members and neighbours were elsewhere, was immense. Their shoulders felt heavy with the responsibility to bring the others back.

“If I can’t bring the others back home, what is the point of me coming back alive?”

The pandemic was especially hard-hitting for the sex work industry. In order to survive, numerous sex workers started taking loans out from vicious loan sharks and private lenders who charged them interest ranging from 60% to 300%. Not only does this put them at the risk of exploitative labor, but their children are also left to face the consequences. The vicious cycle of poverty is allowed to perpetuate because in the eyes of polity and law, sex works are not categorised as migrant workers or daily wage labourers. This left them bereft of the access to government schemes like Jan-Dhan accounts, ration reliefs and health services.

As several media and study reports have highlighted, the violence perpetrated against children, and amongst families of survivors, as well as domestic violence within the confines of homes, is at an all-time high since the lockdown. Since the entirety of the police force have been deployed on Covid duty, there isn’t anyone to even lodge an FIR, let alone take any action.

“The pandemic has revealed to us the interdependence in our societies, as well as how disconnected we all are from each other. This is not about a particular class, caste, or religion; or who has suffered more or less. This connects all of us, yet we are hesitant and ashamed to speak of this impact of interconnectedness. The helplessness of "what should we do?", has been shared by all across-- development workers, corporate human resource officers and government officials so even the shared helplessness connects us, I think,” emphasises Uma.

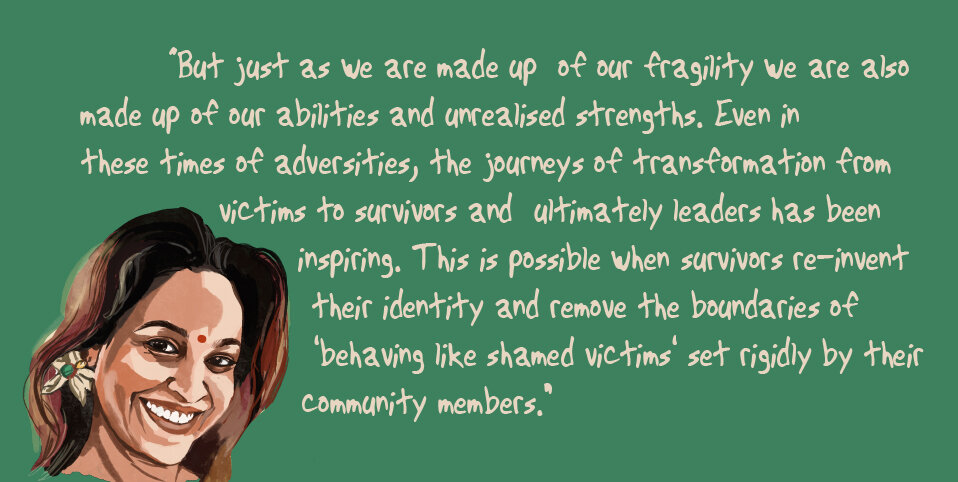

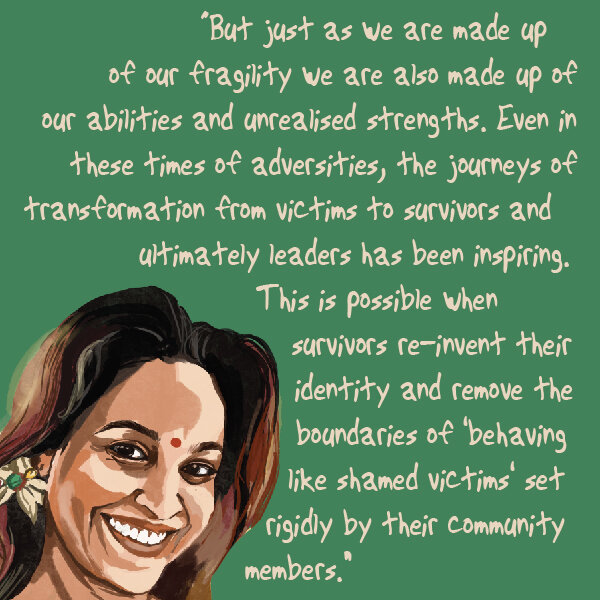

She goes on to talk about being ‘Anti-Fragile’ ( a concept framed by Nassim Taleb in his book ‘Anti-Fragile’), where often people respond to uncertainty and stress by becoming more resilient.

“But just as we are made up of our fragility, we are also made up of our abilities and unrealised strengths. Even in these times of adversities, the journeys of transformation from victims to survivors and ultimately leaders has been inspiring. This is possible when survivors re-invent their identity and remove the boundaries of "behaving like shamed victims" set rigidly by their community members. I remember, immediately after the Amphan cyclone, the government was providing relief for which an application form had to be filled online. Lilufa, one of the survivors, mentored by Sanjog, got trained on how to fill up this digital format through her phone, availed this opportunity and received the relief. And it seemed like almost the entire village then realised this as her power and requested her to fill the forms for them and their families to access these relief amounts. Lilufa would listen to their painful narrations of destruction of their homes, sit with them and patiently fill up their forms through her phone. Her pain of being the "the girl who brought shame" was erased in those weeks and it erased all the limits ( 'lakshman rekha' ) the people around had set earlier. She broke free from these limits and shackles of labels.”

“What has also got me charged is the increase in efforts of collective outreach in rural and urban communities. People have gone out of their comfort zones and mobilised finances, food and medicine. Stories of how people have overcome corruption and violence, to find hope and celebrate small wins, really inspire me.”

Uma shares that her deepest insight in these times has been that Compassion is the capacity to live in the collective.

“When one has the ability to carry on, when one can choose action, even in the face of a threat, share and listen to experiences in these lived moments, and only when we are able to see the inter-relatedness around us, can we overcome this pandemic. Please have the capacity and compassion needed to live in the present moment and recognize the need to choose hope and the courage of vulnerability,” finishes Uma, with a flourish.

Interviewed by Nida Ansari

Edited by Shayontoni Ghosh

Illustration by Anushree Agarwal