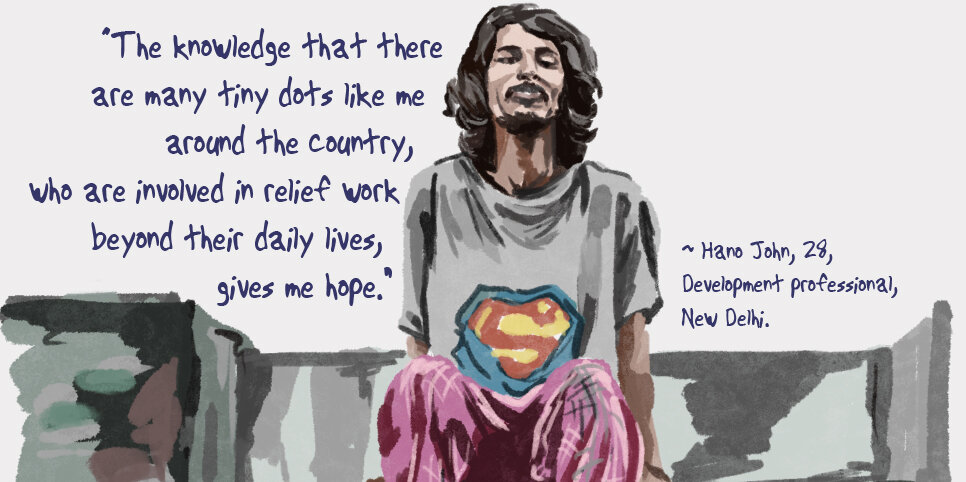

Hano John

“I could not stay at home and do nothing when thousands of people were starving on the road. With so much despair around, knowing that I can return to the safety of my home, I needed to use my social capital for good. I had already been involved in community organizing and student protests since December in the anti-CAA-NRC movement and relief work post the North East Delhi riots. So providing relief during Covid 19 was only natural. “

Hano John, is a 28 year old development professional trained in youth work from New Delhi. During the Delhi North-East riots in February, he started working with a group ‘Rebuilding Livelihoods’, supporting the victims of the pogrom to rebuild their homes, shops, businesses and become financially able. The pogrom relief work overlapped with the lockdown and they extended their efforts by providing relief focussing on North East Delhi. As the lockdown came into full effect they realised that they needed to expand their work to reach more people across Delhi. He and a few friends started the ‘ Covid Volunteer Response’ Team which started providing ration to communities in need, especially the migrant population.

The pandemic brought out a sea of challenges for those living on the margins.

“What really depressed me was just the sight of migrants walking back home for miles. If I had to go deliver food or rations to a 100 people, there were always more people left unfed. We were not only battling Covid but also growing polarization and extreme communal attitudes everywhere. While distributing ration, we would often be asked where the ration came from, and to donate only to a ‘particular’ community. In quarantine centres, people were refusing to eat food because lower caste people had cooked it. There was a huge anti-poor bias .”

But people persevered in their shared struggles, and there was solidarity and resilience amongst them, shares Hano.

“With the Covid-19 volunteer response team, we distributed 500 ration kits to families, on the eve of Eid, ‘chand raat’. Later that night, one person who I had delivered ration to, called me back, thanking me for helping him and his family on Eid. He was sad about not being able to celebrate a decent Eid with his family but said that our relief work brought some happiness to his family, who were already struggling with the effects of the lockdown. In that moment I realized that helping someone isn’t a ‘one way street’, but about building relationships with strangers, who you would otherwise never interact with, thanks to the echo chambers of existence.”

“Once I went to distribute food to Mustafabad, we had ration kits for only 50 families, whereas the requirement turned out to be for 57 families. The community there came together and said , ‘ We will manage’, and distributed food from their own kits to the people who were left behind. The will of communities to become more sustaining and self-reliant, taking care of their own and making sure no one is left behind, was very strong and inspiring.”

“ It's not just a basic threat to survival, but a lack of belongingness, which is making people, leave.”

While scores of migrants had turned their back on the cities they had built, Hano found some who chose not to migrate back. “While writing case studies of low income group teachers who work with children of migrant labourers, I found that parents of these children chose not to go back because they got something beyond food and ration support from these teachers. They felt like someone was looking out for them in this unknown city. The knowledge that there are many tiny dots like me around the country, who are involved in relief work beyond their daily lives, gives me hope.”

Ask him about his vision for a post-pandemic world, and he says, “I see the world changing definitely and this change is not going to be decided by policies made by a few men sitting in one room. The change is being decided and led by communities and leaders from those communities. A cyclic effect that started with the Anti-CAA-NRC movement, today, young leaders are emerging from within the community itself, taking charge and making sure that no one is left behind. Common people, especially young people are stepping up to the challenge of running initiatives, whether big campaigns or small fundraisers to raise money and feed families through those proceeds.”

“Relief work is not just charity but building a community of relationships. We are now slowly realising that we are all a part of an interdependent system where one cannot exist without the other,” concludes Hano optimistically.

Interviewed by Nida Ansari

Edited by Anjani Grover

Illustration by Anushree Agarwal